Sadness has always fascinated artists. It lingers at the edge of beauty, giving form to what cannot be spoken. Across centuries, painters, poets, and now digital creators have tried to capture its quiet gravity—the way sorrow shapes color, gesture, and atmosphere.

The aesthetic of sadness is not about despair, but recognition: the moment when emotion turns visible.

In wall art and prints, this emotion still resonates. From muted palettes to symbolic imagery, the visual language of melancholy continues to draw us in—not because we enjoy suffering, but because sadness makes beauty more human.

From Sacred Sorrow to Romantic Melancholy

In early religious art, sadness was sanctified. Medieval painters portrayed mourning not as weakness but as devotion—the Madonna weeping not for tragedy, but for love’s endurance. The expression of sorrow became a visual prayer, transforming pain into grace.

By the Renaissance and Baroque periods, this emotion deepened into introspection. The melancholic temperament—once a sign of genius—was linked to creative depth. Artists like Dürer and Caravaggio infused their works with shadows not just for realism, but for psychological resonance.

Sadness became a mark of intellect, of seeing too much.

The Romantic Century: Feeling as Form

In the 19th century, the Romantics made sadness their muse. Pain was no longer a burden—it was proof of depth, sensitivity, and truth. From Caspar David Friedrich’s solitary figures to Turner’s dissolving horizons, emotion became the central subject of art itself.

This tradition still lives within modern wall prints—in foggy landscapes, blurred portraits, or abstract shapes that evoke longing rather than clarity.

Melancholy, in art, has never been about defeat. It’s about the dignity of feeling.

The Modern and Postmodern Era: Irony and Fragment

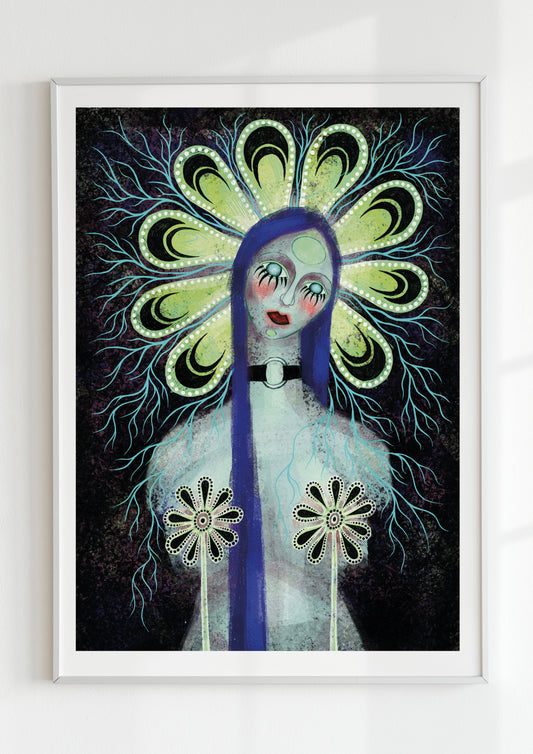

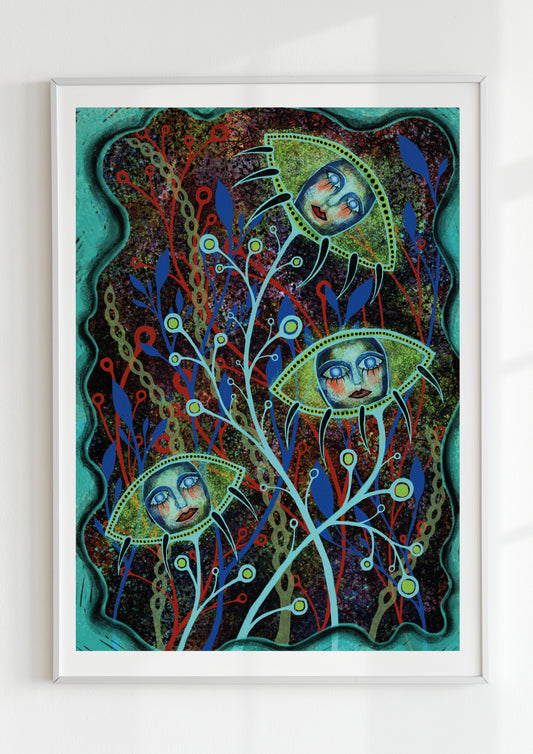

As the 20th century unfolded, sadness fragmented. Expressionists screamed it in color; Surrealists dreamt it in distortion. Later, Pop Art masked it beneath irony—smiles hiding existential fatigue.

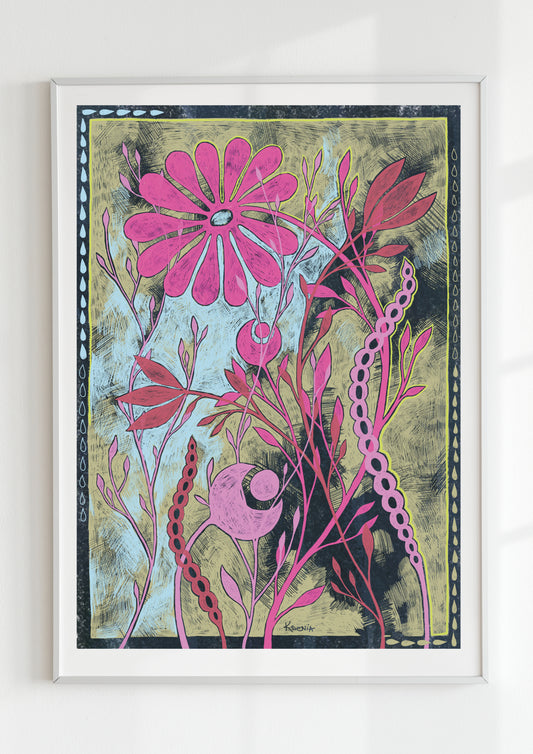

In our own age, symbolic wall art often channels that complexity: eyes crying chrome tears, wilted flowers painted in hyperreal color, rooms filled with quiet electric blue. Sadness becomes a form of beauty that acknowledges fracture, not perfection.

The aesthetic of sadness has evolved from divine suffering to human reflection.

Color as Emotion

Every era has painted sadness in its own hue.

The Renaissance used blue for mourning and serenity; the Romantics used gray to soften grief; the Modernists shattered sadness into abstraction—black and crimson, absence and pulse.

In contemporary art prints, muted tones and fading gradients still evoke melancholy. Pale lilacs, dusty blues, and soft shadows create atmosphere rather than statement. These works don’t cry; they breathe.

They make sadness visible, but also livable.

The Intimacy of Melancholy in Interiors

To bring sadness into the home through art may seem paradoxical—but it creates balance. A melancholic wall print doesn’t darken a space; it deepens it. It turns surfaces into emotional landscapes.

Hanging such artwork is not about decoration—it’s about resonance. It says: I am human. I have felt. I still do.

In minimalist interiors, these quiet pieces anchor emotion. In maximalist spaces, they bring pause between bursts of color. In every case, they whisper authenticity.

Why Sadness Remains Beautiful

Sadness persists in art because it dignifies the act of feeling. It slows us down, draws us inward, and reminds us that life’s quiet moments are as meaningful as its triumphs.

To live with art inspired by melancholy is to make peace with imperfection. It’s to see emotion not as a flaw, but as depth.

The aesthetic of sadness teaches us that beauty and loss are twins—that to create, we must first feel.