In every era, art has served as a vessel for what a culture remembers — its myths, its fears, its songs of survival. Today, as digital noise drowns the whisper of heritage, original folkloric paintings emerge as contemporary memory-keepers. They carry the rhythm of ancestral stories while speaking in a modern visual language, reminding us that folklore never really dies; it transforms.

The Living Thread of Folklore

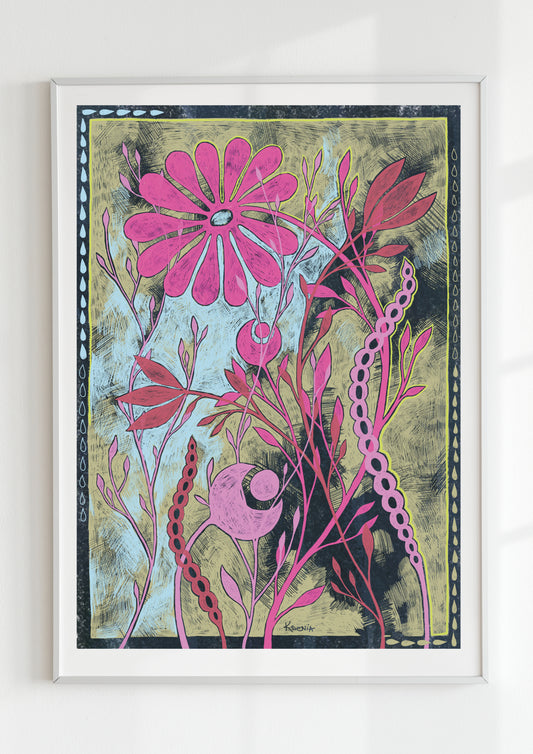

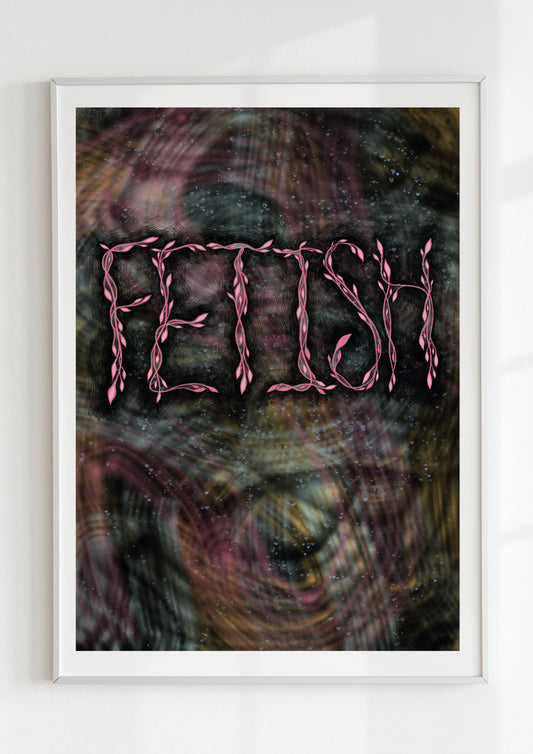

Folklore is not a museum artefact — it’s a living current. Each generation reshapes it, retelling the same archetypes in new voices. In contemporary original artworks, folkloric motifs reappear not as nostalgia but as reinvention: symbols once carved in wood or woven into fabric now bloom in acrylic, metallic pigment, and mixed media.

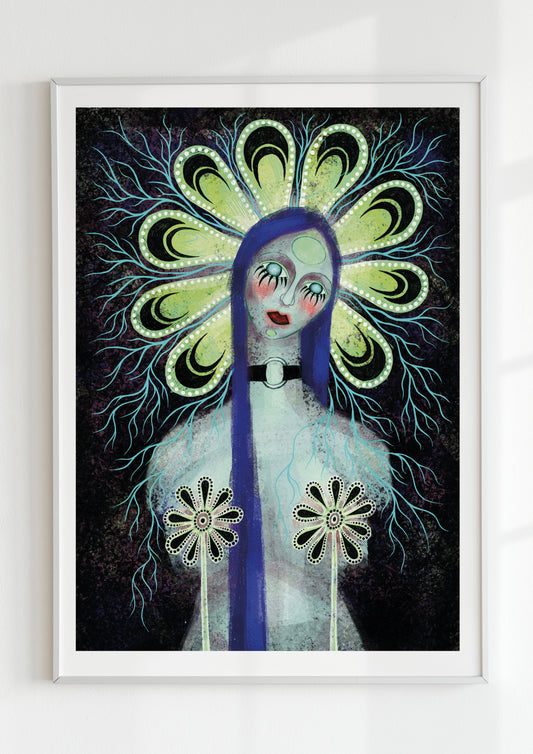

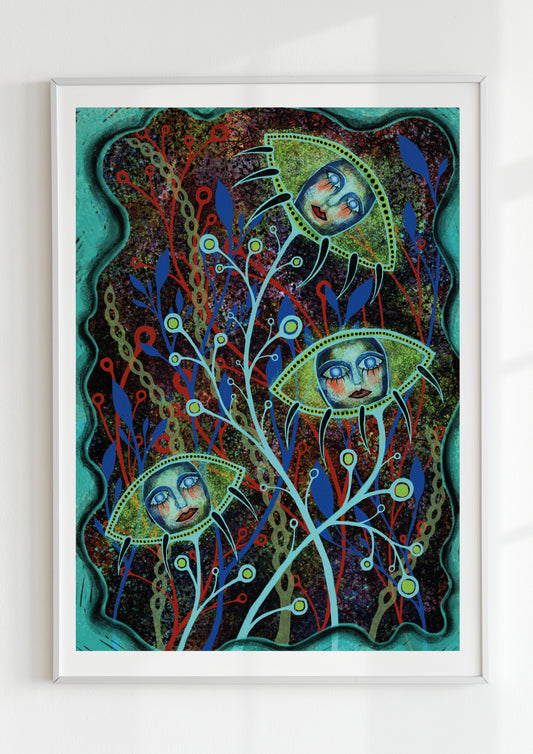

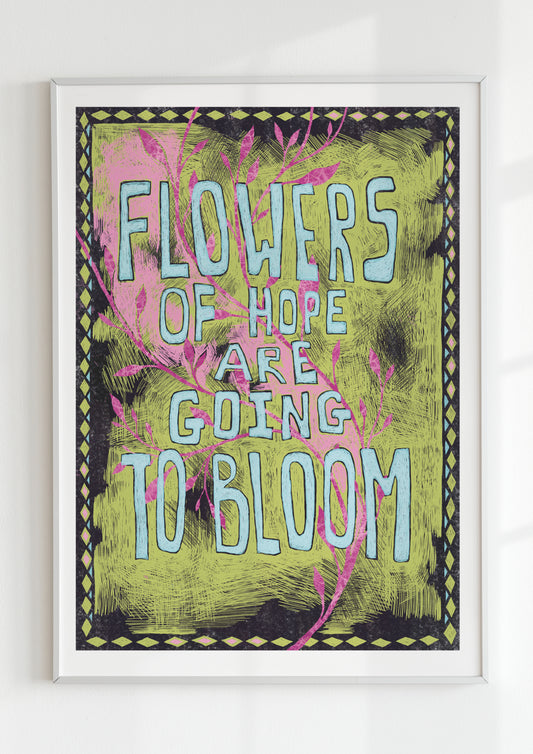

Eyes, flowers, suns, and serpents — once charms of protection — become psychological icons, charged with modern emotion. The pattern repeats: the ancient merges with the intimate, myth becomes metaphor. Through this synthesis, folklore evolves without losing its pulse.

Painting as Cultural Memory

To paint folkloric imagery today is to participate in an act of remembrance. The artist becomes archivist and interpreter, translating intangible heritage into tangible form. In original paintings, every stroke can echo ritual — the repetition of pattern becomes invocation, the layering of pigment a meditation on continuity.

These works hold more than aesthetic value. They are emotional records of a collective past — villages that vanished, traditions unspoken, songs half-remembered. Yet they also resist sentimentality. Instead of freezing memory, they let it move, breathe, and adapt.

The Symbolic Language of Folk Motifs

Traditional folklore always encoded survival through symbol. Flowers were never just decoration — they spoke of life, death, fertility, and resistance. Hands meant protection; birds meant freedom; spirals meant eternity.

In modern folkloric paintings, these symbols resurface with new resonance. A protective eye becomes an emblem of awareness in an age of constant visibility. A serpent transforms from fear into fluidity — the courage to shed and begin again. Folklore adapts to new anxieties while keeping its spiritual integrity intact.

Between Tradition and Modernity

The tension between past and present is where the contemporary folkloric artist thrives. Painting on paper or canvas with acrylic, graphite, and chrome, the artist bridges ritual and modernity — using ancient symbolism to express present emotion.

The folk impulse, once communal, now becomes introspective. The painter’s gesture replaces the collective chant; the studio becomes a shrine. What was once sung or embroidered now takes form through texture and color — proof that art still carries the same human need to connect, remember, and transcend.

Folklore as Personal Mythology

For the modern viewer, original folkloric artwork becomes not only cultural but deeply personal. We recognise fragments of ourselves in those archaic forms — the longing, the cycles, the search for meaning. Folklore survives because it adapts to our private myths; it mirrors our own struggles to belong to something larger than the present moment.

In this way, the folkloric painting functions as both relic and revelation — a link between ancestry and individuality, between what was and what continues to unfold.

To collect or live with original folkloric paintings is to honour memory without freezing it. These works remind us that art does not preserve the past; it keeps it alive.

Every line, every symbol, every flower that defies time becomes a quiet act of remembrance — a bridge between worlds, painted by hand, carried by soul.